Finance professor Mbodja Mougoué returns to Senegal this summer and continues the work he started as a Fulbright recipient to stabilize Senegal’s food prices.

When WSU Ilitch School of Business finance professor Mbodja Mougoué received an email from a woman who claimed to be his former student and a high-ranking official in the Senegalese government, he didn’t know what to think.

“At first I thought it was a scam because she sent me an e-mail saying I’m so-and-so, and I’m the Minister of Commerce in my country Senegal, and I’d like to speak with you about a matter of concern to us,” explains Mougoue. “I thought it was a scam.”

It wasn’t. This email would be the beginning of a long-running project to shape the future of the Senegalese economy and allow Mougoué to pursue an experience he sought all his life.

Originally from Cameroon, Mougoué came to the United States to pursue education and opportunities that were not available to him in his home country. In 1992 he began an assistant professorship at Wayne State University and was later promoted to full professor. It was then that he decided it was time to give back.

“When I was growing up in my village, there were two American programs that were very popular. The Fulbright is one, and the other is the Peace Corps,” explains Mougoué. “We were blessed to have a couple of peace corps volunteers come through, and that sort of prompted my curiosity. I was like, wow, you mean I can travel the world and try to make a difference in people’s lives?

“When I finally was at a point in my career where I could give back, I said well, I think it’s time for me to consider the Fulbright.” Mougoué applied and received a Fulbright fellowship in Côte d’Ivoire, or the Ivory Coast, during the 2000-2001 academic year. His plan was to study the coffee and cocoa industry, and its effects on the local economy.

“I left Detroit, and I was flying through Heathrow Airport in London. I got a message that I should go back to the United States because it was no longer safe to travel to Côte d’Ivoire,” says Mougoué. “I had relatives in London at the time, so I stayed, and I think three or four days later I got clearance to continue.”

Although he was able to complete a year of Fulbright research, further political and social unrest resulting in massive student protests throughout the country hindered his ability to travel and conduct his work.

After returning to the United States, Mougoué reapplied for the Fulbright several times, looking for a new opportunity to give back unhindered by external forces. Initially he did not receive a posting, as the Fulbright committee tends to select scholars who have not previously been awarded.

This changed when Mougoué reconnected with a former student, who was seeking to solve Senegal’s problem with food price volatility.

“When prices go up, I mean they go up like crazy you have 20%, 30%, and in a poor country that can be unbearable, that’s really shocking,” explains Mougoué. “The goal was to see whether we can install something like the futures market that exists in the United States. If we can create a futures market that will solve that problem.”

With classes and other work at Wayne State University, Mougoué wasn’t able to uproot and move to Senegal, which brought him back to Fulbright.

“I wrote up my project and explained to the Fulbright Foundation what I would do if I were to be awarded this prize, that it would be very meaningful not just to me but that here’s a project where you’re making a difference in people’s lives,” says Mougoué. “They found the project worthy of finance.”

Mougoué hoped to establish a pilot program that would target rice, onions and peanuts, and provide a legal infrastructure for farmers to sell their harvest at a stable price, before the food is grown.

“If the farmers know that they can make a simple calculation, that in three months they will have a yield of so many tons, they can sell right now even though they don’t yet have it and they are able to lock in a price and avoid excessive volatility,” explains Mougoué.

A project of this scale requires a lot of groundwork. To enact change in Senegal, Mougoué needed the blessings of the local authorities, and needed to convince small-scale farmers in every corner of the country that this would be a beneficial program.

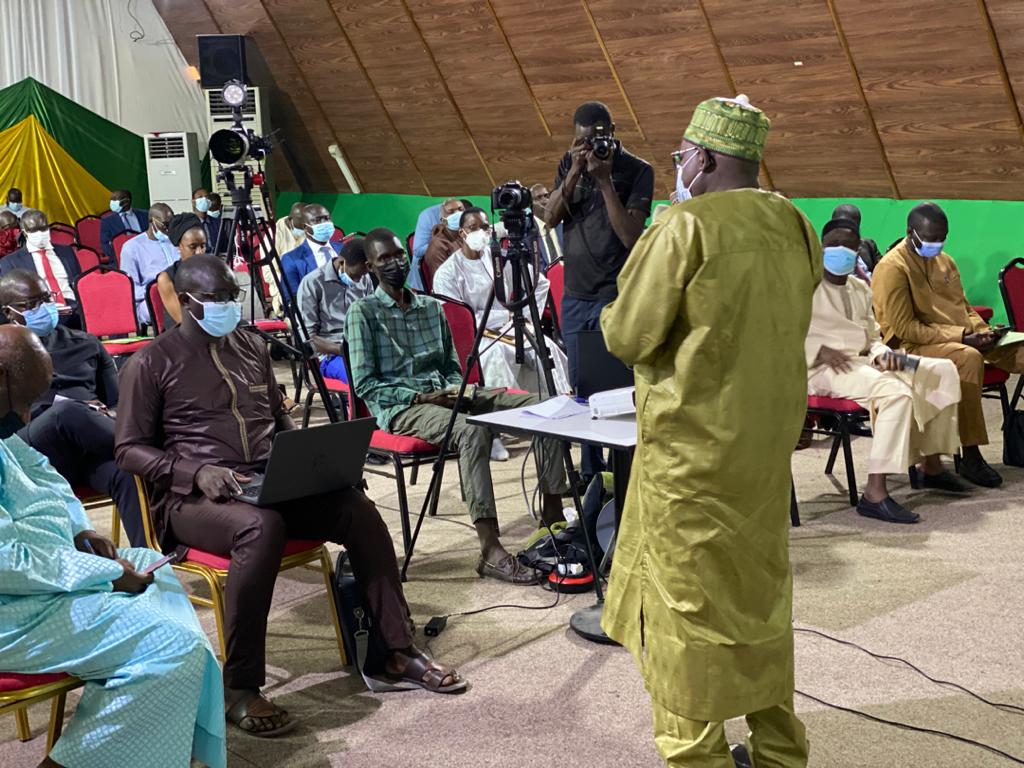

“This involved canvassing the entire country from north to south, east to west,” explains Mougoué. “I mean literally visiting almost every major city, meeting with all the economic agents involved in the agricultural sector, farmers small and large scale, and the political leaders. Everything seems to be interconnected.”

As barriers were crossed, others revealed themselves. After establishing futures contracts at 500 kilograms of rice, Mougoué then had to convince small scale farmers to form cooperatives, pooling together their harvests to reach the minimum contract amount.

Even aspects of Senegal’s infrastructure needed to be reworked to fit into his plan. Old grain silos that contributed to product loss needed to be rebuilt, along with state-of-the-art facilities to store other produce like onions that are essential to traditional Senegalese cooking.

After a year working on the project, Mougoué and the team that he put together to execute the project were far from finished. Mougoué returned to Senegal in the summer of 2023 at the request of the government to continue his work.

“At first I underestimated the amount of work that went into it,” says Mougoué. “It turned out to be a lot of work. But I’m optimistic at this point. The last 25% has proven to be difficult but I think we will overcome it.”

This final 25% includes officially launching the pilot program that would target rice and begin the process of trading futures contracts and finishing construction on the new silos and facilities. On his return to Senegal, Mougoué traveled to the southern region of the county to visit the construction sites where the new silos are being built.

Even with all of the work Mougoué has put into the project, it is slow going, and with an election fast approaching, the clock is ticking.

“The current president Macky Sall and his government are firmly behind the project,” says Mougoué. “What’s going to happen when a new president takes office? Are they going to kill the project, or treat it like it doesn’t exist? I’m hoping we can get this off the ground before the current president leaves.”

Mougoué is hopeful that this project will take root, and that through this he will be able to make a real impact on people’s lives.

“This is not just an academic exercise. This is something that has the potential to affect human beings in a real way, which is why I’m so invested in it,” says Mougoué. “I’ve always wanted to give back and I cannot think of a better way to do that.”

-Patrick Bernas, Information Officer III